TRUSTING YOURSELF MORE THAN YOU TRUST OTHERS

WHEN I WAS A STOCKBROKER, it never ceased to amaze me that when I could buy

the exact same stocks for my clients, some would always make money and some would never make money.

When brokers find stocks they like, they try to do what is called building a position in the stock—buying lots of it for their clients. For instance, if I liked widget stock, I’d call every single client I had to tell them all about widgets.

Then I’d say: “How many shares would you like, five hundred or one thousand?” I was taught in stockbroker training school never to ask a “yes” or “no” question when trying to make a sale. By asking whether clients want five hundred or one thousand shares, you leave the client only with a choice of how many they want, not whether they want them. I was a good salesperson, so most of my clients would buy stock in Widgets at, let’s say, $85 a share. Now let’s suppose all of a sudden Widget cuts its dividend, and before you know it, the stock is down to

$40 a share—and my phone begins ringing off the hook. Some people would invariably say, “Sell, sell, I don’t want to lose more than half my money!” In those cases I had no choice but to sell their stock. Some of my other clients, in for a longer haul, even though they might not have been happy that the stock was down to $40, still knew that this was a

good company and that in time it could come back. Often they would buy more shares at the lower price. Before you knew it, widgets were at

$120 a share. All of my clients had bought the same stock. Some had made money, and some had lost it. By the way, if you think I’m exaggerating the way stocks move, I’m not.

It also worked the other way around. Let’s say this time I was building a position in lobster pots, and all my clients bought it at $6 a share; before long, it went up to $12 a share. Big increase. I’d call my clients and some would say, “Okay, sell it,” and others would say, “Let me think about it,” then call back to say, “No, let’s see if it will go a little higher.” All of a sudden something happened and the stock fell, to $4 a share. All the people who didn’t want to sell it at $12 now got frightened and sold at a loss.

Over the years I started to notice that the people who lost money in either of these ways were always the same ones. They’d sell too soon or too late, but they always lost money. In the business, we called them clients with the “kiss of death” when it came to their investments.

It bothered me when my clients lost money, and I began to think more about it. Finally I realized that it wasn’t a matter of luck, but a matter of, well, spirit, for lack of a better word. It was the attitude, the instinct, with which the client went into an investment that helped to determine whether he or she would make money or lose money. Of course there are good investments and bad investments. But however solid the investment, the investor has to be solidly behind his or her investment as well.

I began to see, too, that the questions I had been taught to ask as a broker worked very well for me—I was rich in commissions—but often worked less well for my clients. I changed my approach. I began really talking to my clients about how they felt about investing in the stock market in the first place. The ones who invariably lost money said that it made them nervous, that they didn’t like it. I asked them why then they invested in stocks, when there were so many other excellent places to put their money, and their answer changed my life: “Because you told me to, Suze.” They were trusting me more than they trusted themselves.

From then on, my heart just wasn’t into selling stocks the way it had been. I can date the beginning of my financial advisory practice from the moment I asked my first client, then the second and third, how they felt

about buying a stock, rather than asking whether they wanted five hundred or one thousand shares. If there was any hesitation whatsoever, I began to suggest that clients pass. I suggested that they pay attention to that little voice inside them, because what it was telling them was what was right for them to do. In 1987, I left the corporate brokerage world to start my own firm, where I could really give advice that was good for my clients, not just good for me. Now I give advice in my books that is good for anyone with financial concerns.

I got this broker and told him to buy me one thousand shares of Atari. When I hung up the phone, I felt terrific about placing this order. Atari was around $4 a share, and I had read these articles about how they had all these great things going for them—and I have to admit I loved playing those games on the TV set when they first came out. I just thought, Go for it. I had this extra money that I was saving to invest, and I was so excited. I told all my friends before I did this, and everyone tried to talk me out of it, even this one adviser friend I have who said, “I wouldn’t do that if I were you.” But I went with my gut feeling.

Within two weeks the stock was at $8! I couldn’t believe it; I had doubled my money. When my friends heard this—of course I called them all up—they were so sorry they didn’t listen to me. In fact, a few of them decided that maybe it would go up more and bought some. Even my adviser friend started to buy it for his clients. It stayed at $8 for a little, and then I started to get this feeling that I should sell. So I called my adviser friend again—why, I do not know

—and asked what he thought. He had just bought it at $8 for all his clients, and what could he think? That it would go up some more. I stayed for a few more days but still feeling I should get out. It went down to $7, but everyone kept saying not to worry, they would announce a deal or something and it would go through the roof. My husband needed a new car, and I kept thinking, Well, just cash in, we’ll have enough for a car. But I didn’t. To make a long story short, Atari did announce this new deal, and before I knew it, back it was at $4. So why did I end up listening to everyone else?

If Janet had listened to that voice in her gut, she would have doubled her money. If her friends had listened to their own voices inside them, they wouldn’t have lost money. If her adviser friend had listened to his own inner voice, he wouldn’t have lost money for his clients and himself, if he had invested, too, although it’s worth knowing that many advisers don’t have the money to invest in their own advice, nor are they obliged to. That little voice inside each of these people, perhaps dozens of people all told, was trying to protect them. None of them trusted themselves more than they trusted others. As a result, they all lost.

![]()

YOUR EXERCISE

When it comes to every financial decision you will make for the rest of your life, you will choose correctly if you go with the answer that reflects your instinctual response. That answer will always be the right answer for you, the answer that will empower you to make money for yourself.

Please go into a quiet room by yourself. Sit there for a moment in silence—no computer, TV, phone, children. Place your hand exactly on that part of your gut that tells you when you’re nervous about anything; you know the place. As you contemplate the following scenarios, take careful note of your very first response, how nervous or confident you feel about each answer that comes to you right away, before you start to rethink it. You should begin to see how you feel emotionally about investing and about planning for your future and how much you trust yourself.

![]() Your

best friend, who’s smart but has never been known for financial

expertise, comes to you all excited. He’s heard about this up- and-coming technology stock from another

friend of his: a sure bet, he says,

a once-in-a-lifetime thing. He’s investing everything he has, and he just knows he’ll

see a payback in a month. Would you like to join him?

Your

best friend, who’s smart but has never been known for financial

expertise, comes to you all excited. He’s heard about this up- and-coming technology stock from another

friend of his: a sure bet, he says,

a once-in-a-lifetime thing. He’s investing everything he has, and he just knows he’ll

see a payback in a month. Would you like to join him?

![]() You’ve

helped your sister find a new apartment. The rent is fairly high, and because she’s just out of

college, the landlord wants you to cosign the lease. Would this be a good idea?

You’ve

helped your sister find a new apartment. The rent is fairly high, and because she’s just out of

college, the landlord wants you to cosign the lease. Would this be a good idea?

![]() Your

parents just gave you one thousand shares of a stock they bought

years ago, in a company

that has done well for them all this time. Your own financial adviser wants

you to sell it and invest in a company she likes better. What would you do?

Your

parents just gave you one thousand shares of a stock they bought

years ago, in a company

that has done well for them all this time. Your own financial adviser wants

you to sell it and invest in a company she likes better. What would you do?

![]() Your

company has a 401(k) plan, and you’re presented with choices about how you want to invest your money—conservatively, with a modest but guaranteed return; or aggressively, with higher-risk investments but a greater chance for real growth.

You must decide by tomorrow.

Your

company has a 401(k) plan, and you’re presented with choices about how you want to invest your money—conservatively, with a modest but guaranteed return; or aggressively, with higher-risk investments but a greater chance for real growth.

You must decide by tomorrow.

![]() You are self-employed and you have all

your retirement money in a SEP-IRA in a respectable mutual fund. You read in the newspapers that the manager

of your fund, which has done well for you, is leaving

the company under

mysterious circumstances and starting up another fund

of his own. The stories

seem to suggest that maybe you should transfer the money to this new fund. What do you think?

You are self-employed and you have all

your retirement money in a SEP-IRA in a respectable mutual fund. You read in the newspapers that the manager

of your fund, which has done well for you, is leaving

the company under

mysterious circumstances and starting up another fund

of his own. The stories

seem to suggest that maybe you should transfer the money to this new fund. What do you think?

![]() Your

new brother-in-law is a financial adviser, and a successful one at that. Your money is doing well in a

mutual fund, but he says he can make it do better by playing the stock market, if you trust him with it.

Your

new brother-in-law is a financial adviser, and a successful one at that. Your money is doing well in a

mutual fund, but he says he can make it do better by playing the stock market, if you trust him with it.

![]() You

are offered a job with a new company that’s just starting up, and you like the people a lot. The salary

is about the same as you’re making

now, with room to grow as they do, but you wouldn’t be getting all the benefits you have with your

present company—no 401(k), no insurance.

You feel there’s such energy behind these people, and they really want you. But you’re old enough

that you are really beginning to think

seriously about the future, and you also feel safe where you are. What should you do?

You

are offered a job with a new company that’s just starting up, and you like the people a lot. The salary

is about the same as you’re making

now, with room to grow as they do, but you wouldn’t be getting all the benefits you have with your

present company—no 401(k), no insurance.

You feel there’s such energy behind these people, and they really want you. But you’re old enough

that you are really beginning to think

seriously about the future, and you also feel safe where you are. What should you do?

There are no right answers to these questions and no wrong answers. Instead, the exercise is about getting in touch with your inner voice so that you can begin to listen, really listen, to what it has to say, because this voice will tell you what’s right for you to do. All the brilliantly conducted research in the world about an investment, all the enthusiasm and salesmanship of a broker, all the hype in the press about this company or that one, none of it means a thing if the pure voice inside you says it’s wrong for you to do. You are far better off taking no action than taking an action that feels wrong to you. Sure, it’s fine to ask around and learn what others are doing, but to be able to act upon what your own feelings and thoughts tell you to do is a priceless gift that only you can give yourself. This kind of power comes from trusting yourself more than you trust others.

There is not one adviser out there who wants to lose money for you, I can promise you that. The good ones would probably rather make more money for you than they do for themselves. It’s also true that financial advisers are real live human beings with feelings, insecurities, bills to pay, dreams of their own, pride, and ego.

Imagine the pressure. Most people don’t want to deal with their own money, so try to think how it feels to be responsible for dozens of other people’s money, their livelihood, their futures. Think how an adviser feels if she recommends an investment to you that she can’t afford to invest in herself. Is she telling you the right thing to do? Think how she feels if she’s also investing in the stock herself—will it cloud her judgment? The pressure, particularly if the broker is a caring person, can lead to what I call the jitters, which is not a good state in which to make important financial decisions.

The jitters occur when raw nerves take over and important decisions about money, which after all are decisions about people’s lives, are made from fear and nervousness, rather than from that pure inner voice and true knowledge.

Suppose an adviser has built a tremendous position in XYZ stock. As he sits at his computer, he watches every time XYZ moves up and he watches every time XYZ moves down. With every tick down, his phone rings and it is a client asking about XYZ; with every tick up, he awaits the next tick down, he gets jittery; the notion hits him that maybe it’s time to sell.

Now he starts punching in the symbol of that stock over and over again to get more detailed information than what the screen normally tells him. He watches the volume: What do others who are selling know that he doesn’t know? He looks at the bid, the ask, the research reports.

What do they really mean? He calls a few of his friends who also have a position in the stock, to see what they think. Even if none of these people had been thinking sell, even if they reply, “Well, I really still like the stock,” something happens. Doubt has a domino effect; I’ve seen it.

Meantime the supervisor walks by to remind the adviser, who works on commission, that he hasn’t met his sales quota this quarter. To do so, he must buy some more stocks on his clients’ behalf or sell some more. Then his wife calls. They need a new furnace. Then a colleague he sits near starts jumping around with joy—another stock she has built a position in has just gone through the ceiling. She begins making excited calls to tell her clients the great news. Then our adviser hears a tick and looks at the screen: XYZ is down another one-half point.

After a few hours of this, the adviser makes the decision, calls his clients, and sells the stock. End of jitters? No way; now the real test begins. If the stock starts rising, the phone begins ringing with clients wanting to know why he sold so soon. It’s almost harder not making as much as could have been made in a stock than it is to lose some and feel relief at not having lost everything. The whole experience goes into our adviser’s jittery memory bank and is automatically recalled the next time he thinks about buying or selling.

It takes an extraordinarily disciplined person to overcome these jitters and to make continually intelligent decisions based on his or her pure inner voice and what can be learned about a stock. It takes even more discipline to believe what you know when the jitters of other people who happen to own the same stock as you are spreading through a brokerage firm like the flu.

If you decide you want to go with a broker, fine. If you already have a wonderful broker who has so far done very well for you, even better. Best of all is if you decide to handle your own money and feel powerful and confident about doing so. In any case, though, it is your money— and it must be guided by what your inner voice tells you to do.

With most of us, decisions come, decisions go—we make them and deal with the consequences when we have to. But we all make decisions about our lives, financial and otherwise, all the time: What kind of a car do I think I should buy? When do I think I should buy it? Where should I send my child to school? What color should I paint the bedroom? Do I really want to go to dinner at the Wentworths’ on Saturday night, with such a busy week ahead and my proposal due at work on Monday? Is such-and-such an issue worth the fight it’s going to cause if I bring it up with my partner? Might this or that stock that I keep reading about be a good stock to buy?

Such decisions come up every day, and always that inner voice is there to guide us in making them wisely—if we let that voice have its say. When these decisions come up, I am asking you now to start keeping track of them: What was the decision that had to be made? What did your inner voice, your first instinctual response, tell you to do? What did you actually do? Please write down the answers and keep them wherever you keep the monthly bills. Now see how the decisions played themselves out, depending on whether or not you followed your voice. Should you have painted your bedroom that ivory, which was your first impulse, instead of the yellow? Should you have bought a new car when you knew you should have, before the old one collapsed for good? Did the stock you were thinking about in fact go up? Didn’t you really know deep down inside that little Jenna would be better off at a school that was less competitive?

You will see the results for yourself. Testing your voice will enable you to trust it. It’s your voice, and when you begin to take action based on what you yourself truly believe, you’ll begin to feel power over your life —and over your money.

When I first started out at Merrill Lynch, money market accounts were just beginning. Mutual funds numbered in the low hundreds and hadn’t yet been embraced by a wide range of investors, much less changed the way millions of us now invest for our futures. Exchange traded funds (ETFs) did not exist. Discounted ways to invest were just starting, which meant that the most common way into the stock market was through a full-service company like mine. With a full-service brokerage firm you’re paying full-service prices: you’re paying for their real estate, their overhead, their business lunches, their advertising, their commissions on all kinds of brokers. These firms are reputable, certainly, and once you read the rest of this chapter about the language and workings of investment, you may even decide that the way you wish to be respectful to yourself and your money is to have an adviser at a full-service firm, fees notwithstanding. As for the discount firms, they’re thriving. Why?

Because smart consumers always flock to where they’ll get the best deals for their money. On their way, they stop to study what they’re buying and where they’re buying it.

There’s also a language of money, and by the time you finish this book you will know it.

If you have ten years or longer before you need your money, you must invest, whether in your 401(k) or on your own. And the more you invest, the better. After you finish reading this section, by trusting yourself, you will know which kinds of investments are right for you.

Those investments don’t have to be in the stock market; you can invest in Treasury notes and bonds or in your house. You can decide whether you want to invest on your own or whether you want to go with an adviser. Again, these are decisions you will reach by trusting yourself.

My own opinion is that most people have more than it takes to invest on their own. The information sources on the Web are extensive and accurate. You can learn a lot this way and, just as important, really begin to feel much more comfortable in the world of money. The point is, you must learn the language of investing and have the knowledge to decide what kind of investing is best for you.

There are also plenty of general-interest money magazines out there. And, of course, money is a popular topic on cable television stations, and in most cities there are financial shows on the all-talk stations. Eavesdrop on the world and language of money, and pretty soon you’ll know you belong.

The price of admission to the world of money is lower than you might think and, especially with the onset of mutual funds and ETFs, the easiest and safest way to create your own fortune. Here’s what you need to know.

The goal of each mutual fund is different and, as a result, each fund invests in different kinds of stocks, bonds, or other investments. Some funds invest for long-term growth, some for income, some for a combination of the two. (Growth funds typically invest in stocks of companies that are growing rapidly and whose price per share may increase dramatically in value. Income funds invest in bonds and have a smaller chance of making a lot of money; they generate present-day income—retirees might own these, for example, after they’ve seen their money grow during their working years.) Some invest in stocks just in the United States; some, those known as international funds, invest only in stocks overseas; funds called global funds invest in both. The variations go on and on, but if you have a specific interest, I guarantee that you can find a mutual fund that addresses it. When you invest in a mutual fund, basically you own a tiny fraction of each share of stock or whatever they’ve purchased, so even if you own just one mutual fund, your money is still quite diversified, because you own a little of everything they’ve invested in.

If you had a financial adviser at a full-service brokerage firm like Merrill Lynch, he or she would have to consult you before making any transactions, and you would have to pay a commission almost every time you bought or sold anything. That’s not the case in a mutual fund, where the manager has free rein over the money in the fund and you’re not charged a commission when transactions are made. You will receive a prospectus and information with a breakdown of what the mutual fund has been up to, but you’re not notified day to day. By buying shares in the fund, you have made the decision to trust the fund manager.

A good mutual fund is a great way to invest money, particularly small sums of money: You achieve diversification, commission-free trading within the account, and a professional manager or team of managers who are buying and selling and doing what they think best.

How Is an Open-End Fund Priced?

At the end of each day, the manager totals up the entire value of the portfolio that constitutes this mutual fund. He divides that total by how many shares are owned by the investors. This figure, whatever it comes out to, is called the net asset value, or NAV. It is what each of your shares is worth. If you are a new investor and want to invest $1,000 into this mutual fund, and the NAV that day was $10 a share, you would own one hundred shares of the mutual fund. If the fund’s value goes up by $.25 a share, you will make $25. The more shares you have, the more you make—and the more you lose if the fund goes down.

Rule of thumb: Before you ever buy a managed mutual fund, look to see how long the manager has been in charge. Is the current manager the one responsible for a fund’s good track record, or has that person moved on, leaving someone new in charge? It’s the manager’s track record you want to know about, in other words, not the fund’s, because the manager is the one who creates the fund’s success.

A number of websites monitor the funds—how they’re doing, who is moving on—but the one I like best is called morningstar.com.

There are several indexes that track the values in the stock market. You hear about these every day when you listen to the news and constantly hear the newscasters quoting the Dow Jones Industrial Average. You know how they’ll say, for instance, “The Dow Jones is up twenty-three points today and closed at 11,000.” The Dow Jones average is an index based on thirty stocks. If these thirty stocks happen to go up, so does the Dow Jones average, and if they go down, same thing. I always found it fascinating that so much seems to rest on just thirty stocks, but it’s used widely.

To my mind, a far better index, and one that’s also widely referred to, is the Standard & Poor’s 500 index; also known as the S&P 500. This index tracks five hundred good-size stocks, which is a lot more than thirty. You will often hear this index quoted right alongside the Dow Jones, and when you do, pay attention. This is also a great index because so many people use it to measure the market—which means that many, many experts are keeping tabs on it every single day.

Another very popular index is the Nasdaq. This index currently tracks about 5,000 different stocks, mainly in the technology area. Since its inception in 1974, the Nasdaq index market has been the industry innovator. It was introduced as the world’s first electronic stock market. With the boom and bust of the dotcom stocks, most of you by now have heard of the Nasdaq, and the truth is, as time goes on, you will hear more and more about it.

There are other indexes that track the American and overseas stock markets (as well as indexes that track the bond market, but we are focusing on stocks here); they aren’t quoted as much as the Dow Jones, Nasdaq, or S&P, but they’re also used to track how everything is doing overall. Among them: are

![]() The Wilshire 5000 equity index. This index tracks thousands of stocks of companies of all different

sizes, large and small. It’s also outgrown its name—it really follows almost

seven thousand stocks. Even though it’s not widely quoted, it’s one of the best.

The Wilshire 5000 equity index. This index tracks thousands of stocks of companies of all different

sizes, large and small. It’s also outgrown its name—it really follows almost

seven thousand stocks. Even though it’s not widely quoted, it’s one of the best.

The Russell 2000 index. This index tracks two thousand stocks that are traded on the OTC (over-the-counter) market

![]() The EAFE index. This one owns stocks of companies

based in Europe, Australia, and the Far East.

The EAFE index. This one owns stocks of companies

based in Europe, Australia, and the Far East.

Managed mutual funds constantly compare their performance to that of the various indexes. A fund will boast of “outperforming the S&P 500” over a certain period of time, meaning it increased in value by a greater percentage than did the S&P index. (Of course, many funds underperform the indexes, too.) So one easy and effective way to invest is to buy what’s called an index fund, which simply mirrors an index, by buying all the stocks in the index it is associated with. Its performance will, by definition, match that of the index exactly, whether that’s the S&P 500, the Dow Jones, or the EAFE less the expenses of the index fund. Many mutual fund companies offer S&P index funds, as well as growth, international, and bond index funds, and it’s easy as can be to sign up with one of them.

You should also consider exchange traded funds (ETF). Just like an index mutual fund, an ETF tracks a benchmark index. But it trades just like a stock; in fact, you need to have a brokerage account to buy and sell shares of an ETF. The fact that an ETF trades during the day—unlike a mutual fund where the price is set just once a day after the market closes—can give you the ability to move in and out of an investment at the market price when you place your order. Some people consider that a nice advantage, though when you are investing for the long term, I don’t think that’s too important. You want to buy and hold anyway. But the real advantage of ETFs is that their annual expense charge is even lower than the typical index fund. There are some ETFs that charge just

0.10 percent a year. The largest ETF firm is Barclays, which runs the ishares ETFs; you can learn more at www.ishares.com.

WHICH IS BETTER, A MANAGED FUND OR AN INDEX FUND/ETF?

When it comes to mutual fund investing, it is true that there are some genius managers out there—who can outperform the S&P index in a given year or for a few years. But it is rare for a managed fund to beat its benchmark index on a consistent basis. And many younger funds simply lack the track record to know how they will do over the long term. Remember, when you are investing for growth, you hope to leave your money right where it is for at least ten years. Only time will tell which would have been a better way to go, but if I were a betting woman, I would just stick with index funds and ETFs if I did not want to be actively involved with watching everything about the fund I was in.

Index funds and ETFs have lower fees than actively managed funds and typically generate no, or low, annual tax bills. All this in the end adds to your overall return.

Expense Ratio

Every mutual fund and ETF charges annual expenses, known as the expense ratio. The average is about 1 percent a year for actively managed stock funds. And I’ve seen them higher than 2 percent. Whatever the expense ratio, it will definitely affect your net rate of return. Let’s say that one spectacular year the manager of your mutual fund makes a return of 20 percent. Do you get that 20 percent? No. Before you get your money, the fund subtracts the expense ratio. If the expense ratio is 1.5 percent, your real return will be 18.5 percent.

Some of my favorite index funds and ETFs, on the other hand, have total expense ratios of less than 0.20 percent and do very well, thank you. Why in the world would you want to pay someone to manage your money for you if that manager couldn’t consistently outperform the index that it’s comparing its performance to? You wouldn’t.

Capital Gains Tax

The other advantage of an index fund over a typical managed fund— and this can be major—is that mutual funds are set up so that if there’s a capital gain when they sell a stock, that gain is passed through to the investors. At the end of the year the fund will pay you (or reinvest in the

fund, your choice) all the realized capital gains they’ve acquired that year. Whenever a mutual fund has a capital gain distribution, it also reduces the NAV by the price of the capital gain. Let’s say that you’ve invested in a mutual fund with a NAV of $10, which itself has a capital gain distribution of $1. If you have chosen not to reinvest capital gains, you’ll get $1 for every share you own, and you’ll have to pay tax on it. If you have decided to reinvest the capital gains, then the fund will buy you as many shares as that capital gain allows, but you’ll still have to pay tax on this amount. In addition, in both cases the NAV of the mutual fund has now been reduced to $9 a share. That said, funds you own in a 401(k) or IRA do not owe tax each year; your investments grow tax- defined, or in the case of a Roth IRA or Roth 401(k) tax-free if you follow certain rules.

Maybe this doesn’t sound so bad, but depending on how much money

you have in the fund, you may be unpleasantly surprised to see what this capital gain distribution does for you if it happens to come in a year when you’re in a high tax bracket to begin with. It’s definitely a drawback in a managed mutual fund that you have no say or way to plan in its decision whether or not to take a large gain in a given year. All that fund cares about is making the greatest return for you, which is fair enough. They don’t care whether it’s a convenient year for you to pay taxes on a capital gain.

Happily, this isn’t as big a problem with an index fund. Since index funds buy the whole index, they do not in general distribute capital gains. Why? Because they don’t sell with such planned regularity. They buy and sell when only one of the stocks of the index is removed and a new stock takes its place. Since a fund that matches the S&P 500 index is meant to track the stocks in the index, it has to make these appropriate changes as necessary. But these trades occur with nowhere near the frequency they do with a managed fund. So if the idea of paying taxes on unexpected capital gains worries you, this should be taken into consideration before you decide on a managed fund or an index fund. Exchange traded funds are even more tax efficient; you owe tax only when you sell, and assuming you have a profit.

Remember, it’s not how much you make that counts. It’s how much

you get to keep.

LOADED FUND, NO-LOAD FUND: WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE?

The difference is about 4.5 percent, give or take, out of your pocket.

In addition to the expense ratios that all funds charge, if an adviser suggests you purchase a fund and you do so through him or her, you may also pay the adviser a commission. The average commission costs about 5 percent. The commission is known as a load. Think of it as a burden on your money.

A no-load fund, on the other hand, is a mutual fund you buy directly, and therefore there’s no commission attached to it. In my opinion, no- load mutual funds are the only way to go. Many advisers charge clients a flat fee and use no-load funds. If you work with an adviser, this is the way to go. Think about it. If you were to invest $10,000 in a no-load mutual fund and decided, two seconds later, that you wanted to withdraw your money, you’d get all $10,000 back, assuming the market didn’t move. Loaded funds, on the other hand, would cost you.

The Price of a Load

There are two kinds of loads, a front-end load and a backend load fund. Backend load funds also have a high expense ratio because there is a special fee known as the 12b-1 fee, buried in the expense charge. Sound confusing? It’s meant to be. The people making this money, your adviser or broker, would rather you didn’t know how much you were paying.

Front-end loaded funds charge a load up front. They are also identified as A share mutual funds. When you see the name of the fund spelled out anywhere, if it has an “A” or says “A shares” after the name, then you know it’s a front-end loaded fund. If you invested $10,000 in a 5 percent loaded fund, and decided two seconds later to withdraw your money, you would get back only $9,500—the adviser got that $500. This fund would have to go up more than 5 percent in value just for you to break even.

Funds with a backend load, also known as a deferred sales charge, are even worse.

When mutual funds first came onto the scene, you could buy one only through a broker, so they were all loaded funds. Over the years, though,

many mutual fund companies came out with no-load funds, and slowly but surely investors began seeing their value and investing. This migration was putting a big dent into the profits of brokerage firms that sell only loaded funds, so they came up with a way to make you think you could buy a no-load fund through them: It’s called a backend load fund and it has a big charge, known as a 12b-1 fee, hidden in the expense ratio. Any fund with a “B” after its name levies this fee. Let me explain how this works.

These funds are typically sold to you by a financial adviser. Some of these advisers sell you these funds under the pretense that you are not going to pay a load to be in the fund as long as you stay in it for five to seven years. If you cash out before then, there will be, the adviser will explain, a “surrender charge” starting at around 5 percent and going down by 1 percent each year until it reaches 0 percent. (In a true no- load fund you can cash out the same day without paying a penny.) Not too bad, you might think, since I plan to leave the money in there for a long time anyway, so it won’t really cost anything. Wrong. You will be stuck paying a much higher expense ratio because of that 12b-1 fee I mentioned earlier. It can add 1 percent to your overall expense ratio every year. You need to understand how that extra one percent can add up over the years. If you stay in the fund for fifteen years, and it charged

you a 1 percent annual 12b-1 fee, the cost of that 12b-1 fee is like

paying an extra 15 percent sales commission. Who can afford that?

This 12b-1 fee is in addition to the other fees as well. You’ll also have to pay the management fees and other costs that are part of the regular expense ratio. The 12b-1 fees are put in place to pay the adviser’s fee for having sold you the fund. How it works is that you buy the fund, the brokerage firm advances the broker’s commission to him the day you buy it, and you keep paying and paying so that the firm will get back the money they paid to the broker. Your 12b-1 fee is how they get the money back. If you close the account early, your surrender charge is what guarantees the company it will get back more than it paid the broker: a no-lose proposition for the brokerage firm, but you lose all around.

In other words, these B-share funds with large 12b-1 fees are a rip-off. I would avoid them if I were you. And even though some fund companies now offer a deal where your B-share fund automatically

converts to A shares (they tend to have a lower expense ratio) once your “surrender” period is over, I still think those first few years of paying such a stiff 12b-1 fee is too costly. You really should focus on true no- load mutual funds.

Why Would My Adviser Sell Me These Funds?

Because that’s how he or she makes a living, and you’ve not chosen an adviser wisely. True financial advice is to tell the client how to get the most bang for the buck, even if it means the adviser won’t make a lot of money with the transaction. Advisers are there to help you get rich, not to get rich off you. It’s the adviser’s fiduciary responsibility to tell you if there’s a less expensive way for you to make money—and give you the choice of what you want to do after explaining how much each of your options will really cost you.

But no-load funds can be purchased without the help of an adviser— no middleperson, no commissions, no hidden costs, just smooth sailing to greater and greater wealth over time. And as I mentioned, many advisers in fact use no-load funds and ETFs for their clients, choosing instead to charge a flat fee for their services. Such fee-only advisers are the only advisers you should ever consider. Do you need an adviser? If after reading this next section you feel you do, then you do, for your own peace of mind. But you may just want to test the waters yourself. At my website, suzeorman.com, you can learn about The Money Navigator. This is a monthly newsletter that I launched in 2011 along with economist Mark Grimaldi. The Money Navigator highlights no-load mutual funds and ETFs that Mark recommends for investors saving for retirement. The newsletter also provides recommendations for mutual funds that are popular investment choices in many 401(k)s. You can sign up for a free one-year subscription at suzeorman.com by entering the code “financial freedom.”

TESTING THE WATERS

MY MOM'S STORY

Whether you want to believe it or not, you and you alone have the best judgment when it comes to your money. Here’s a story about me and my mom:

A few years ago, I had a terrific hunch about a particular stock. I just knew it was a great buy, especially priced as it was at around

$1.50 a share. So I told the person that I love most in the world, my mom. My mom has always lived really, really frugally and, since my dad died, has managed to have enough to live comfortably on, but she has never been a great risk taker in the stock market; in fact, she still worries about me when I buy or sell stocks. This time, to my amazement—maybe she caught the excitement in my voice—she said she also wanted to invest in the stock I had chosen—$5,000. Eighty- three years old, and now she decides she wants to jump into the market!

Now—again to my amazement—I began to caution her. Did she understand that any stock that was selling for only $1.50 a share was totally speculative? Yes, yes, she understood that perfectly well. Did she understand that she could lose the entire $5,000? Yes, she understood. She felt the worst-case scenario was that if she lost it all, she would have $5,000 less to leave me when she died. Was I willing to take that risk? (I hate it when she outsmarts me at my own games.) I was willing, so my mom and I invested in the stock that same day, each of us putting in $5,000.

Everything was holding steady pretty much until a few months later, when the stock started to go down and down and down. My mom, who by now was really into this, began calling me up every day and saying, “What do you think we should do?” I would say the same thing I would have said to my clients, “What do you think you should do?” and, satisfied, she’d say, “Let’s just hold it.” That was how I felt, too, until the day the stock hit twelve cents a share, which made me begin to doubt my own inner voice. Five thousand dollars is a lot of money, and this was my very own mother.

That was the day she called up to say, “Let’s buy more.” I couldn’t believe it.

I said, “What did you say?” and she said, “I just have this instinct to buy more.”

When she said this, I’m sorry to say I did not encourage her to follow her instincts. Instead I said something to the effect of, “Mom, are you crazy? This stock is almost belly-up and we can’t throw good money after bad.” I’m also sorry to say that now she began to mistrust her own instincts as well and simply agreed with me. We left our money where it was, but our hopes fell and now we both trusted less in what we had believed about the stock.

To make a long story short, the stock fluctuated between twelve and twenty-five cents a share for almost a year, then: boom. It started to skyrocket, and soon after that we had both tripled our money. One day, while the stock was still at this high, my mom called again. “Suze,” she said, “I’ve decided that it’s time to sell.” This time I didn’t stop her from listening to her inner voice. I said, “Go for it.” She made three times the money she put in, and she was perfectly happy about it.

Even so, my mom would have made ten times, not three times, her money if I hadn’t drowned out her inner voice and made her doubt what she knew to be true for her. If that spark of instinct had been guiding her actions, she would have been far better off than she was by letting my doubts get in her way.

The moral of the story is that—whether you want to believe it or not

—you and you alone have the best judgment when it comes to your money. You must do what makes you feel safe, sound, comfortable. You must trust yourself more than you trust others, and your inner voice will tell you when it is time to take action.

I’m not in any way suggesting that if you take your nest egg and go out and find a speculative stock to invest it all in, you’ll get rich. You won’t. You’ll be a sitting duck if you do that. What is more, I doubt your inner voice would guide you in that direction anyway.

Nor am I suggesting that you shouldn’t listen to others or learn about what you’re planning to invest in. You need information to make good decisions. But your inner voice will help you weigh that information properly. What I am suggesting is that you test the waters before you jump in with everything you have and that you practice listening to that

inner voice. As soon as you see how easy it is to stay afloat, and get used to the investing temperature, so to speak, you very well might want to go in deeper.

GETTING READY TO GET STARTED

It doesn’t matter if you have a large lump sum you want to invest or if you’re just starting from scratch and want to put in a little here, a little there, as you can. Rule number one is that to invest in the stock market (through mutual funds, exchange traded funds, and the like, not just by buying and selling this stock or that one, the way my mom and I did), you must invest only money that you will not need to touch for at least ten years. Why? Because, as we’ve seen, there has never been in the history of the stock market a ten-year period of time where stocks have not outperformed every other investment you could have made.

Not that history always repeats itself, but this is a spectacular indicator. However, if you do not give your money ten years, you will be taking a significant risk. If you don’t have the time to leave this money sitting there, it is possible that when you do need to take it out, that need will arise at the worst possible time. Let’s say you invested in 1999 and were planning to withdraw the money to buy a house within the next four years. You decided, Okay, I’ll just invest in the market, make all I can, and then have more money when the time comes to make the down payment. One year later you find the house you want and make the offer, which is accepted—on April 14, 2000, a day the market goes down considerably, and the day you had decided to sell, for you need your money. You will most likely take out far less than you initially put in. If you could have just waited—but you could not, for you needed the

money to buy your home. So time is everything.

Remember dollar cost averaging (this page)? This is the technique that works so well for long-term growth, in which you are investing wisely by limiting your risk. If you are investing that $50 or more a month, or if you have a huge stash of cash in a savings account that you now feel right about testing the waters with, this is your method of investing, because with dollar cost averaging you raise your chances enormously of ending up a winner.

I am not talking here about you turning into one of those tycoons in B- movies who is always shouting, “Buy, buy, buy,” or, “Sell, sell, sell,” into the half dozen phones on his desk. Instead I’m talking about you venturing into the market in a safe way, spreading your money among dozens or hundreds of stocks, via mutual funds that gifted professionals spend their lifetimes watching and guarding, and having time and the market touch your money with magic. These days the richest and savviest investors may like to shout, “Buy, buy, buy,” or, “Sell, sell, sell,” into a phone from time to time for the thrill (and potential payoff) of playing the market on a hunch or a tip. But these same investors have most of their money exactly where I am going to tell you to put yours: in a safe place, where over time it will grow and grow.

If

you are reading this and still feeling your inner voice say, No, I can’t

do this, it’s not right for me, then listen to that voice and read on, because I will also tell you how to choose an adviser for your money, if that’s what makes you feel best.

But if you can, try testing the waters on your own first. Most people, I find, discover they truly love dealing with their money once they understand how to do it. Just remember: Give your money ten years to grow.

IF YOU HAVE A LUMP SUM TO INVEST

Let’s say you have $20,000 to invest. Maybe it’s sitting right now in a retirement account at work, and you think you might want to be more aggressive with the way in which you invest it—or some of it. Maybe you’ve just gotten an inheritance or a huge raise at a new job. Maybe you’ve just had this money sitting in a savings account, have felt for a long time that you could do more with it than leave it in that savings account, and suddenly decide: Now’s the time. Whatever the case, let’s say it’s $20,000, but it can in reality be more or even much less. Let’s see how to invest it.

So that you can get used to the investment waters, rather than investing 100 percent of it all at once, I want you to divide it up and start investing slowly over the first year, to see how it makes you feel. The chances, I think, are good that by the end of the first year you’ll be

ready to plunge in.

Take 80 percent of what you have to invest, which in our example is

$16,000, and put that money in a Treasury bill or note, or just leave it in your money market or savings account, anywhere it will be kept safe for you for about a year. After that year is up, it will be up to you if you want to keep investing it so safely, invest more on your own, or if you want some professional help in investing it. Your inner voice will tell you which is best for you. Trust yourself.

If these are not funds you are investing within a retirement account, the best way to buy a Treasury bill or note is by contacting the Federal Reserve office nearest you—or by calling 800-722-2678 or visiting www.treasurydirect.gov and setting up what is called a Treasury direct account. This is where you buy your Treasuries directly from the Federal Reserve absolutely free of charge. You could also, if you wanted, buy your Treasuries from a broker, either a discount or full-service broker; but this would cost you about $30, and why spend $30 if you don’t have to? The other reason to buy your Treasuries directly is to get used to them and the way they work (they’re simple!). When it comes time to stop investing for growth, many people transfer some or all of their money from the market into Treasuries and draw the money they need to live on from the interest. This might be part of your overall plan, too, and it’s a great idea to become familiar with how they work right now.

So $16,000, or 80 percent, goes into Treasuries or is just kept safe. The other 20 percent, in this case $4,000, is what you’re going to invest in the market.

When Do I Buy?

Now you have $4,000 and you’re ready to invest. If you were asking me for advice right now, I’d tell you to sign up for a free one-year subscription to The Money Navigator. This is a newsletter I launched in 2011 with economist Mark Grimaldi that provides recommendations on mutual funds and ETFs for your retirement funds. The newsletter highlights funds and ETFs that match your appetite for risk as well as your life stage; typically the younger you are, the more you will want to have invested in stock funds and stock ETFs. You can learn more at suzeorman.com. Enter “financial freedom” as the gift code to receive

your free one-year subscription.

You are not going to plunk down this $4,000 all at once, remember; you’re going to use dollar cost averaging. Divide the amount you have to invest by 12; in this case, your figure would be $333.33.

Now you’re going to take this monthly sum and, on the same day each month, put it into a good no-load mutual fund or ETF month in and month out for the first year, using the dollar cost averaging technique.

You can choose either a managed fund or an index fund or ETF; and with dollar cost averaging the beauty is that when the market goes down, you’ll simply be able to buy more shares. So don’t be afraid. You have plenty of time to let that money sit. Buy, too, when the market is up, because next month—who knows?—it might be up even more. Just buy, each and every month.

After the year is up, you will have a sense of how you felt about investing, whether it felt right to you or not. I have to tell you that nearly everyone I’ve dealt with feels truly powerful once they take the financial reins of their lives in hand in this way; in fact, most people say that if they’d known it was this easy, they would have done it long ago. When the year is up, they usually invest all the rest of their money as well, or whatever percentage they feel comfortable with. Before you know it, using AAII, other publications, and the Web, they have invested in other mutual funds they like, which means they have a diversified portfolio. They’re off and running.

What Do I Buy?

What you will buy will depend in part on how much you have to invest, because some funds have a very small minimum, while with others you need more to invest. The minimum will also vary depending on whether you’re investing in a retirement account or on your own in a regular account. Vanguard, for instance, which is one of the great mutual fund companies, has a minimum of $3,000 if you just open a regular account with them. If you open an IRA at Vanguard, the minimum drops to $1,000. Most mutual funds typically require $1,000 or so to get started.

You have a choice when it comes to buying mutual or index funds or ETFs. You can buy them directly through the fund company itself, or you

can open an account at Charles Schwab, TD Ameritrade, or any of the other great, low cost brokerage companies and buy the same no-load fund through them. (Make sure there is no transaction fee involved; there shouldn’t be.)

Some of the great families of funds:

VANGUARD

800-662-7447

T. ROWE PRICE 800-638-5660

FIDELITY

800-343-3548

WHEN DO I SELL?

There is no harder question when it comes to the stock market. And there’s no single correct answer, because the market never stops going up and down. To answer the question of when to sell, don’t worry about what the market is doing. As always, just keep in touch with your inner voice and your time frame.

The answer will vary, depending on your individual circumstances. If you’re very lucky, you may never need to use this money or need the income it could generate for your retirement. If that happens to be the case, then the answer may be never; you can let your beneficiaries inherit it. Currently, when your beneficiaries inherit something, its cost basis for determining gain or loss for tax purposes is what the inheritance was worth the day they inherited it. So if you bought one thousand shares of stock at $10 a share years ago, and over the years the stock splits and the price rises so that you now own eight thousand

shares at $40, this means that your $10,000 investment is now worth

$320,000. If you sell it, you will owe capital gains taxes on $310,000, the difference between what you bought and sold it for. Now let’s assume that instead of selling it, you left it to your beneficiaries; because they inherited it, their cost basis is what the stock was worth when you died: $320,000. If they then sold it for $320,000, they would not owe one penny of capital gains taxes.

In all likelihood, however, you’re counting on this money for retirement. This means you will one day want or need to switch some or all of your money from growth-oriented investments to an income- generating investment, such as Treasury notes or bills. In any case, you will need to keep a careful watch on that ten-year time horizon.

Let’s say that you have had your money diversified among several mutual funds for nine years already, and you know you won’t need it for another ten years, if then. As long as those funds are performing as well as or better than other funds that are similar to it, just leave it where it

is.

Now let’s say you’ve had your money diversified among several mutual funds for seven years, but this time you know you will probably retire in about three years. At that time you will need this money to start generating income so you can begin to live off the interest that the principal will generate. You will have to make a change. With your eye on your timeline, it is time to start reevaluating right now. Let’s say, too, that you had a great run in the market over these seven years, and you’ve averaged about 15 percent a year on your money.

What do you do? It’s terrific that you’ve done well, but don’t try to outsmart the market. You do not have ten years ahead of you in which you can leave your money just to sit there. Consider taking some of your profits now.

It may turn out that the market suffers a setback, so that if you had ignored your nervousness, you would have been left back at square one. Or the market might skyrocket after you withdraw your money. Who cares? You have made your money. You have listened to your inner voice. You are far better off selling and ceasing to worry than you are letting your fear drain you and make you feel powerless. This is the money you intend to live on for the rest of your life, and you must trust yourself more than you trust others about where to keep the money safe

that will keep you safe.

That said, please think through your retirement time horizon. Just because you may retire in five years, that does not mean all your money should be out of the stock market by the time you retire. The fact is, you could spend twenty to thirty years in retirement. Consider that the average life expectancy for a sixty-five-year-old male is seventeen years, and for a sixty-five-year-old female it is twenty years. That means that half of today’s sixty-five-year-olds will still be alive—and needing money

—well into their eighties and a portion of those people will still be alive in their nineties. With the prospect of such a long life, you should consider keeping some of your retirement money in stocks, even after you are retired. Not all, and certainly not most of it, but some of your money belongs in stocks. Because stocks, over the long-term, have the best prospect of generating inflation-beating gains for you.

If, however, you have ample money that you are confident you will be just fine living off the income generated by your bank accounts and bond investments, that’s great. Just make sure that you have accounted for the fact that over twenty years a 3.5 percent rate of inflation will reduce the purchasing power of $1 to about 50 cents. If your conservative investments earn less than 3.5 percent, you may have a hard time keeping up with the price of things in twenty years.

Plunging in Deeper?

Once you have invested for a year, you may decide, as thousands of other people have, that yes, you’re up to the task and ready to plunge in deeper. Watch carefully over what you are creating, keep in mind your time frame, and listen, always, to your inner voice.

If instead, after this first year of investing, you find you’re not comfortable with it, and your inner voice says that you would rather have professional help before you plunge in deeper, then again, you must listen to that voice. And you must find the very best help you possibly can.

FINANCIAL ADVISERS

MY STORY

If after I became a broker, any of my clients had ever asked me— and thankfully no one ever did—what I had done for a living before I went to work for Merrill Lynch, I would have told them the truth: Before becoming a broker, I worked as a waitress at the Buttercup Bakery in Berkeley, California. My dream was not to become a broker, but to open a hot tub and sauna place, with a restaurant and haircutting salon built right in: one-stop shopping if you happened to want a meal, a haircut, and a sauna. I would go on and on about this dream to my regular customers, and finally one day a man named Fred Hasbrook gave me a check with a letter that read, “For people like you to have your dreams come true. To be paid back if you can at 0 percent interest in ten years.” I was stunned, and even more stunned as word got around and others of my regulars chipped in, too. Believe it or not, I soon had a $50,000 nest egg with which to start my business.

At the suggestion of one of my benefactors, I put the money into an account at Merrill Lynch and was assigned to a broker, a sweet guy whom I’ll call Rick. I told him I wanted to keep my money safe, and he had me sign some papers that I didn’t even read. Off I went, to have blueprints for my business drawn up. I still have those blueprints.

To make a long story short, that sweet Rick—knowing that the money wasn’t mine, knowing that I wanted above all to keep it safe, and knowing that it was being held there so I could open my business

—had me investing in these things called options on oil stocks, the most wildly risky and speculative investments I could have been in. I felt funny about this from the beginning, but I didn’t know enough, or trust myself enough, to understand why or say no to Rick’s grand schemes. In the end, I agreed because I trusted Rick. With his nice office and pin-striped suits, he was the closest I’d ever been to Wall Street or big money. At first we were doing pretty great. In those early weeks we were up $5,000. I couldn’t believe it! I had never

made so much money without even trying, so I became totally

intrigued with this new way to make money and thought that I had better study up on this great new moneymaking discovery.

This was in 1979, before anyone had computers at home, and I was trying to figure out about these options from reading the newspapers every day. I had stock quotes and options quotes pasted up all over my bedroom walls, trying to make sense of them. Finally I began to get the hang of it and understand what we were doing—and how what we were doing was very, very wrong for me. My understanding came too late, I’m afraid. The reversal of oil stocks happened quicker than you could say sauna and hot tub, and I lost it all, all the money I had put in and all the money I had made. Everything. My financial “adviser” had done me in, not to mention what he had done to all those people who had tried to help me.

It took me a long time to get a true understanding of what it takes to handle other people’s money. It is not like Monopoly, when after you’ve finished playing the game you simply take the houses off Park Place, pack up the money that comes with the game, and go on with your day. So much more is at stake.

Rick may have been my broker, and a reckless if not unscrupulous one at that, but I couldn’t have been luckier that he was at least with a reputable and nationally recognized firm like Merrill Lynch. Merrill came through in the long run and covered the losses in the account, after I demonstrated that he had misled me about the risks inherent in what we were doing, so in the end I was able to pay back all the money to my investors. I had picked the right firm, at least, if not the right broker at the firm—and both decisions are extremely important if you decide to go with a full-service brokerage firm.

Soon afterward, I joined Merrill Lynch.

Why would Merrill Lynch hire a waitress? They weren’t hiring a waitress. What they saw in me was that I would be an excellent saleswoman, and they were right.

At major brokerage firms, the brokers or financial advisers (which is what I became at Merrill Lynch) are mainly commission-based advisers who do not usually come up with the ideas of what you should buy or sell. Most of them take the recommendations of the financial analysts

who work for the firm. Your adviser takes these recommendations, checks to see whether they’re suited to your needs and financial situation, and tries to sell these investments to you if they (and you) meet those criteria.

My story about Rick isn’t meant to frighten you out of asking the help of an adviser, if you feel that’s the way to go. Nor is it meant to suggest that all advisers are disreputable, because most do have your best interests at heart and, if the firm itself is reputable and you yourself trust the adviser, you will almost certainly be safe. By turning your money over to someone else, however, you must not give up feeling responsible for it, as I did when I signed those papers. The ultimate responsibility for your money must always remain in your own hands.

WHAT DO FINANCIAL ADVISERS DO?

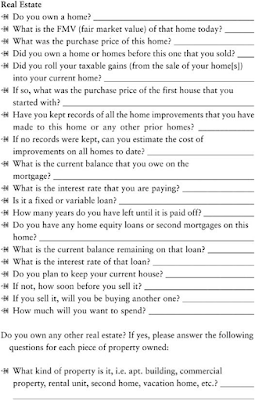

Many people I speak to tell me one fact and one fact only about their lives: how much they have to invest. This tells me nothing about them and nothing about their financial situation. If someone says she has

$10,000 to invest, but also has credit card debt of $8,000 at 18 percent, it may be that her best investment of all would be to pay off that debt first thing. If someone is going to be looking after and investing your money, that person should know everything in your financial picture, including how you feel about risks and what your goals are—the questionnaire I used to send my clients (this page) will give you an idea of what a concerned and competent adviser will always want to know.

If you’ve joined the AAII, you will see that there are many different titles and certifications of advisers or planners, some far more qualified than others. Some will just provide you with a financial plan and send you home to carry it out; some will be on your payroll for as long as you want, taking care of your money. You won’t want, for example, the adviser you hire to be licensed only to sell you securities. You want to know that your adviser cares enough about managing money to have gone to extra lengths to become a Certified Financial Planner® professional (this is what I am). A Certified Financial Planner® professional has had to pass a series of exams that deal with every aspect of finance, including risk management or insurance, retirement planning,

taxes, and estate planning. It usually takes two years to study for and pass these exams, and those who do pass are required to stay up-to-date by taking continuing education courses and to abide by the standards of the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards, Inc. (the CFP Board; visit their website at www.cfp.net).

HOW MUCH DO FINANCIAL ADVISERS

CHARGE?

When you go to interview financial advisers, you are considering whether you want to hire each one: You are the boss, regardless of how much they know about money. You are the boss of your money, and when you hire someone to take care of it—just as when you hire a qualified gardener to look after your garden or a qualified child care worker to take care of your child—you are the boss of that person as well.

When I was seeing clients, I set up my own, somewhat unusual, fee schedule with this in mind. When someone—rich, poor, doesn’t matter— called my office for an appointment, that prospective client was first sent a letter stating what they were expected to bring along to the appointment and explaining my fee structure. About a week later my secretary almost always would get a call from them saying that the only thing they were having a hard time with was how much I charged. My fee structure dictated that clients must pay me what they thought my services were worth to them. At the end of our session, which ran an average two hours, they decided what my services were worth. My clients were the boss.

Apart from my way, there are a few ways that advisers charge for their services.

FREE CONSULTATION

An adviser who sees you for free is trying to convince you to hand over your money to him to invest for you—and reap the commissions for himself. Since mutual funds, if purchased through an adviser, carry heavy commissions, around 5 percent, most likely mutual funds will

make up a hefty part of your portfolio if you go with this adviser. So if you go in to see an adviser for free, so to speak, and hand over $20,000 for him to invest in those loaded funds, then you will have paid $1,000 for that “free” session. The second that you sit down in that office and tell the adviser how much money you have to invest, he knows what it means for him. If you come in with $100,000, he’ll get about $5,000. Not bad for an hour or two of work.

FEE-BASED

This is where you simply pay the adviser an hourly fee to tell you what to do with your money. She does not do it for you.

FEES PLUS COMMISSIONS

You pay the adviser a fee to tell you what to do, to create a plan with your money. If you decide you’d like him to implement it for you, he’ll also get a commission.

REGISTERED INVESTMENT ADVISERS (RIAS)

Another option is to hire a registered investment adviser (RIA), who will create, in effect, a personal mutual fund for you and serve as the manager of it. RIAs usually require a large minimum to start with, ranging from $50,000 to $5 million, with the average minimum being about $250,000.

An RIA manages your money for you on an ongoing basis, for a fee that is usually a percentage of the money you’ve given her to manage. This percentage can range from .25 to 3 percent a year, but you should not pay more than 1.5 percent including all commissions. Think about this. The amount you pay is a percentage of the money she is managing: Isn’t this a great incentive for her to make your money grow? If you gave her $100,000 initially, and by the end of the year you had $200,000, if you were paying her 1 percent, she’d have made $2,000. (And I hope you would send her an enormous bouquet of flowers as well.) If you lose

money, she loses, too. This is an adviser who is truly on the same side of the fence as you and whose compensation is attached to a real incentive to make money for you.

Most RIAs will ask you to sign what is called a discretionary account trading form, where you give the RIA permission to trade your account without getting your permission for every transaction. This is absolutely the only time you should even consider doing something like this. You must still make sure that your money is held in a reputable institution like TD Ameritrade, Charles Schwab, or Fidelity, for example, and all the RIA has the right to do is buy or sell, not withdraw money except for any fees she is owed.

Not many RIAs buy mutual funds because it does not make sense to pay the RIA 1 percent a year to manage your money and also to pay the full expense ratio of the mutual fund. If you decide to hire an RIA, please find out what she invests in before you sign on.

INTERVIEWING A FINANCIAL

ADVISER

If you’re in a domestic relationship, you must both go to see the adviser. (I wouldn’t see clients who were married or living together unless they came in together.) Before you do, I urge you and your partner to have a talk about what you want to accomplish with the adviser and the fears about money you have and make sure you both have a thorough understanding of where you stand right now. After you’ve chosen an adviser, you must make all decisions as a team and both be kept up-to- date with what the adviser is doing.

I met so many people, women in particular, who didn’t have a clue what to do when their husband or partner died or when they went through a painful separation or divorce. I also saw how bewildered many people became when their parents died, leaving them an inheritance. When you have suffered a loss, you are in a state of grief, and this is not the time to make major financial decisions. Run as fast as you can from an adviser who suggests big changes at this time. My advice is to leave your money in a high-interest-bearing account for between six months and a year, until your inner voice feels okay about doing something with these funds. To be respectful of your money, you must give yourself time to heal.

If you and your partner are interviewing an adviser together, you must both feel comfortable talking to him intimately about your money. The adviser should address you both equally, give you plenty of time, and answer questions and explain fees in a way you can easily understand. You should also be comfortable with the kinds of investments he suggests and understand everything about them when he explains them to you. If he fails to meet any of these criteria, find another adviser.

When you interview anyone for a job, it is up to you to outline your requirements. For example, here are several expectations you should have for a prospective financial adviser:

![]() That

she will call or e-mail you every time she makes a change in your account (unless she is an RIA).

That

she will call or e-mail you every time she makes a change in your account (unless she is an RIA).

That she will explain in thorough detail why she wants you to make every new transaction

![]() That

she will tell you without your having to ask if she is selling something for you that’s not in your

retirement account, fully explaining the tax implications.

That

she will tell you without your having to ask if she is selling something for you that’s not in your

retirement account, fully explaining the tax implications.

That she will explain every commission

![]() That

she will never pressure you into doing anything that does not feel right to you.

That

she will never pressure you into doing anything that does not feel right to you.

![]() That she will send you a confirmation

from the brokerage firm that holds your money, telling

you what’s been bought or sold. This confirmation must always match transactions you gave permission for.

That she will send you a confirmation

from the brokerage firm that holds your money, telling

you what’s been bought or sold. This confirmation must always match transactions you gave permission for.

![]() That she will send you a monthly

statement summarizing all that month’s

transactions, including deposits,

withdrawals, and current

positions held. This statement must come directly

from the brokerage

firm that’s holding

your money, not from your adviser’s office.

That she will send you a monthly

statement summarizing all that month’s

transactions, including deposits,

withdrawals, and current

positions held. This statement must come directly

from the brokerage

firm that’s holding

your money, not from your adviser’s office.

![]() That she will prepare both quarterly reports

and an annual report that will tell you the exact return

she is getting on your money, as well as all fees and commissions. The figure on her report must match the report that is generated directly from

the brokerage firm. These reports should

also show you all the realized gains or losses (all the money you actually made or lost from selling an

investment) and all the unrealized gains and losses (investments you own but have not yet sold and thus

That she will prepare both quarterly reports

and an annual report that will tell you the exact return

she is getting on your money, as well as all fees and commissions. The figure on her report must match the report that is generated directly from

the brokerage firm. These reports should

also show you all the realized gains or losses (all the money you actually made or lost from selling an

investment) and all the unrealized gains and losses (investments you own but have not yet sold and thus

that have not yet realized a profit or loss). These reports should also include returns of the overall index, so you know whether you’re doing better or worse than the index. You want everything in writing.

![]() That she will never ask you to write a check made out to her personally.

All the money that is handed over needs to be placed in an institution (Schwab, TD Ameritrade,

Vanguard, or the like), and every check

is to be payable to the institution. This is absolutely essential. More than one “adviser” has flown the coop with dozens of clients’ money.

That she will never ask you to write a check made out to her personally.

All the money that is handed over needs to be placed in an institution (Schwab, TD Ameritrade,

Vanguard, or the like), and every check

is to be payable to the institution. This is absolutely essential. More than one “adviser” has flown the coop with dozens of clients’ money.

That she will return your calls in a timely manner

That she will always get you the information you request about an investment and find out any answers to questions you have that she doesn’t know

![]() That she will keep you informed about your money,

not just call you when she wants

to buy or sell something. If a stock

has gone down,

or is not performing the way she expected it would, you are to hear about it from her, not read about your money first in the newspapers.

That she will keep you informed about your money,

not just call you when she wants

to buy or sell something. If a stock

has gone down,

or is not performing the way she expected it would, you are to hear about it from her, not read about your money first in the newspapers.

You should type up all these requests on a piece of paper and have your adviser sign an agreement to do all the above.

NOW THE ADVISER MUST INTERVIEW

YOU

Just as important as what you ask the adviser is what the adviser asks you. Remember: People first, then money.

I learned, in my practice, that I got a better understanding of my clients when I went over the topics on my questionnaire in person with them, rather than having them fill out the answers on their own. Sometimes people had a hard time writing things down or tended to leave things out, so talking through the questions enabled me to find out more about my clients than simply reading through hastily filled out answers. Other advisers feel that this is too time-consuming, but this process is not about saving time. It’s about saving—and making—money. Whether your prospective adviser has you fill out the form or talks you through it, it is absolutely essential that you feel this person wants